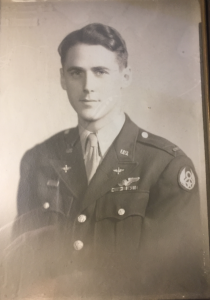

I called my 91-year-old uncle last week to let him know wife Ann and I were in Walla Walla, Washington. This out-of-the way small American city which we were passing through on vacation was where as a young flight officer/navigator, he met up with his 10-man B-24 flight crew in 1944.

Uncle John (mom’s bro) and I got to talking yesterday about how he ended up in the Army Air Force (AAF) and the places his training took him around the U.S. Indeed, it was a circuitous and illogical route that only the military could dream up.

But at a tender age, he saw a lot of the country and the world, some of it at its worst.

As a 18-year-old, he joined the army in 1943 and started out at Fort Devens in Ayer, Mass. Later at Fort Jackson, S.C., he happened to walk by an AAF recruiting office. Bayonet practice had not gone well so he walked in and applied to be a fly boy (I suspect many infantry enlistees had the opposite sentiment and did not want to fly).

Two weeks later, he was on his way to Miami to begin AAF training.

This began a zig zag course across the nation. His memory of what he did in all these locations is a bit fuzzy, but it might have been not much. In typical Army fashion, his crop of AAF recruits, he told me, had to stay at the same level of training.

He spent several months in each place. All his U.S. travel was done by train, sometimes standing up. He has never been much of a traveler so his treks as a teenager and young 20 something strike me as all the more remarkable.

From Miami, he went to Syracuse, N.Y. to the university bearing the same name and presumably learned something, but he cannot recall quite what. He also managed to squeeze in a couple of trips home to Concord, N.H.

Then it was on to Louisiana for navigation school. Most likely, that was at Selman Field in Monroe. After that, he headed to Fresno, Calif., probably at Hammer Field, which specialized in night flight operations.

And finally he landed in Walla Walla for his crew assignment and to practice bombing almost assuredly at the Army Air Base. He assumed that his crew would be sent to the South Pacific given their western location. Nope. It was back to New Jersey to eventually board the New S.S. Nieuw Amsterdam luxury liner for the trip to England.

Why did the military have him end up in these western locales and direct him back east? “You’d have to ask them,” he said, a master of understatement.

From an airbase in Harrington, England, he flew 20 missions as a Carpetbagger in the 8th Army Air Force. The Carpetbaggers (technically, Operation Carpetbagger) dropped spies and weapons to The Resistance in Europe. And my uncle’s unit did high altitude night bombing on industrial targets and dropped surrender tickets.

Most of his missions were flown in February and March, 1945 and he has a book about the Carpetbaggers where he checked off the missions in which he participated.

The danger from flak or enemy fighters was much reduced by then, but by no means was it safe. There still was some ground fire and his crew was told if they bailed out in the North Sea, nobody would come for them.

The war in Europe ended and he fully expected to be sent to the Pacific. His crew flew to the Azores and on to Newfoundland where they spent a week because the skies and airports were thick with returning aircraft. They stepped back on U.S. soil at Bradley Field in Hartford.

He can’t recall exactly where he was sent next, but he remembers it was the Midwest. One thing he recalls about that location is a bar where a guy wearing mittens played the piano. “He was pretty good,” uncle John says with a smile.

Like so many small town boys and girls who’d never been much of anywhere (No Disney World in those days), he took his wartime travels and duty in stride. It was a remarkable time in our history. Thank you, uncle John, for your service and being such a wonderful part of my life.

One more thing: had we not dropped The Bomb, I may have never known my Uncle John or his family. He left the service in late 1945 and eventually earned a civil engineering degree from RPI on the GI bill. Thereafter, he spent 39 years with the Maine Dept. of Transportation building highways.

4 comments On Playing the piano wearing mittens – a WWII travelogue

John, Stunning writing and an incredible chronicle.Kudos

jimF

Thanks, Jim. Uncle John is a very humble and quiet man (typical engineer). He liked millions of others (and you) uncomplainingly did their duty.

Thanks, John, for filling in a few blanks about Dad’s life. Over the years, he talked about his experiences back then in pieces, but your story puts the whole thing together sequentially. A few details I hadn’t heard, like the piano player with the mittens.

John, thanks for dragging that info from my dad. When I was young, he never wanted to talk about the war. One little tidbit– it got so cold in London that winter they would burn vinyl records to keep warm. Also one time had to chase his service cap halfway across London because of the wind!

Sliding Sidebar

Blogs and Sites TDR Likes

Subscribe