Read Nov. 26, 2019 to the Tuesday Night Club

“In rocky cathedrals that reach to the sky” — John Denver, The Eagle and the Hawk

Donner Pass has always fascinated me. As mountains forming the boundary between Nevada and California, the pass and the Sierra Nevada Range have an insanely rich history with a little bit of everything — heroic rescues, unfathomable determination, tragedy, mystery, cannibalism, starvation, loss, triumph, racism, treachery and pioneering that endured unimaginable hardship, much of this buttressed by the rugged individualism woven into the American soul.

This rocky cathedral may not have been where east ultimately met west on the transcontinental railroad, but it was hands down the most dramatic and difficult stretch of that Herculean feat of engineering. Its highest railroad tunnels have been silent since 1993 when a lower tunnel was enlarged to allow double stack containers and trains heading in the opposite direction to pass each other. Today, the ghostly tunnels attract hundreds of curiosity seekers who can’t resist the short hike from the roadway. The farther you go into them, the darker and spookier they get.

One’s mere presence in Donner fires the imagination and gives rise to the voices of the past. Railroad men, valiant Chinese laborers and names like Donner, Stanford, Crocker, Huntington, Hopkins and Judah come to mind. It was civil engineer Theodore Judah who mapped the route up and over Donner and convinced the Big Four back him. It wasn’t just a crazy idea. It was insane.

Bounded in the east by Truckee and Colfax in the west, Donner is 52 miles of some the most inhospitable winter terrain anywhere. The Pass averages 411.5 inches of snow a year. Record snowfall was set 1938 with 775 inches only to be outdone by 800 inches 14 years later. That’s 66 feet and 14 sixes to right of the decimal point.

In January, 1952, an epic storm stranded Southern Pacific’s crack train, The City of San Francisco and its 196 passengers for three days near the Donner Summit. I quote from Tahoetopia.com, a local information portal.

“Even as the blizzard raged on, Southern Pacific rescue trains were inching their way closer from both east and west toward the stranded streamliner. One train carried dogsled teams. The Sixth Army trucked in Weasels (over-snow track vehicles) and soldiers trained in winter survival. Military doctors and nurses were rushed to likely rescue points near the stranded train. During a brief lull in the storm, a Coast Guard helicopter managed to drop medical supplies and food.”

Donner is big, nasty, majestic, spiritual and beautiful. In good weather, you can run up and over it on I-80 in a little more than an hour. But you’d be selling yourself short if you didn’t take scenic Donner Pass Rd., which more or less follows the railroad and provides story boards and turns outs so motorists and cyclists can soak up points of interest.

Let’s back up to March, 1846 when Capt. George Donner published an ad in the Springfield, Ill Journal which began: “Westward Ho! For Oregon and California. Who wants to go to California without costing them anything.” Indeed, his wife Tamsen had written in a letter that 7,000 wagons would cascade into California in 1846 (the Gold Rush was still two years away). Lured by free land, the Donner Party left Springfield, Ill. on April 16, 1846 with a stop in Independence, Mo. May 10th to pick up provisions.

When the group reached Fort Laramie by early July, they were urged to stay on the tried and true Oregon Trail instead of taking a shortcut known as the Hastings cutoff. Expecting to be led down the Hastings cutoff by its namesake trail blazer Lansford Hastings, the 20 wagons of the Donner Party headed to Fort Bridger and down the cutoff. It was a decision that sealed their fate.

They arrived exhausted and hungry in late October at the eastern approaches to Donner Pass in what today is Truckee. The weary pioneers had disintegrated into scattered parties and were low on provisions. The weather was about to turn foul. Truckee was named after a Paiute chief who guided parties, often stressed, hungry and lost, over the pass, including Gen. John C. Fremont and Kit Carson one or two years before the Donners.

The trudge across the grassless and parched Great Salt Lake had exacted a huge toll on the Donners and their animals. It had come on the heels of a difficult descent through the canyons of the Wasatch Mountains. Native Americans picked off their cattle, horses and oxen, many of which were near death from starvation and thirst. The decision ran against the advice of the trail’s namesake founder, Lansford Hastings. His advice to stay on the less harrowing but longer Oregon Trail from Fort Bridger in Wyoming never reached the Donner party. Hastings and others correctly believed the rough trail would not accommodate Donner’s heavy wagons. Hastings was also supposed to guide them on the cutoff, but had left with another party before the Donners reached Fort Bridger.

Following an eight-day blizzard in the early November, several attempts were made to conquer the Pass. All were turned back, primarily due to the heavy drifts. Finally, a group of 17 including women and children left Truckee in mid December, 1846. After 33 days of wandering lost and starving, a handful of survivors made it to Fort Sutter thanks to Miwok native Americans who rescued them. Cannibalism is highly suspected by the survivors. They even ate the ox hide webbing in their crudely assembled snowshoes. Such desperation, but at the same time, a will to live at any cost.

Also, James Reed made it out of the Sierra Nevada in October after he had been banished by the group for stabbing a teamster to death during an argument. He would later form rescue parties, but men and supplies were difficult to cobble together because the Mexican American was raging further to the south in California.

Of the 87 in the Donner party, 48 survived with 34 perishing between October,1846 and April, 1847 – 25 males and nine females, many children. Cannibalism was likely but never proven and only passed down anecdotally to historians such as Charles McGlashan, who dubbed the first group to make it out “The Forlorn Hope.”

Of local interest is Tamsen Eustis Donner, Capt. George Donner’s wife. She grew up at 50 Milk St., in Newburyport, Mass. The handsome and restored tan gambrel still stands today and was occupied for 50 years by the grandparents of one of my high school classmates. Tamsen, a teacher from a well-to-do seafaring family, is described as energetic, religious, barely five feet tall and 100 pounds.

When you enter the Donner Party Museum in the west end of Truckee and adjacent what today is Donner Lake, there’s a prominent story board with an ironic quote from Tamsen: “If I do not experience something worse than I have not yet done, I shall say the trouble is all in getting started.” The passage was printed in the Springfield Journal on July 23, 1946 and reflected the Donner’s relatively smooth passage across the plains. The treacherous the Hastings cutoff loomed.

Tamsen, 38, married George Donner, 54, in 1839 after meeting him in Springfield, Illinois where she had gone to teach and take care of her widowed brother’s children.

Tamsen had been widowed and George was twice a widower. Her first husband, North Carolinian Tully Dozier, had died in December, 1830. The preceding month, she had given birth to premature daughter who died on Nov. 18. And she had lost her beloved son on Sept. 28. While dying young was hardly the exception in those days, losses so close together must have devastated her.

She survived possibly to early April, 1847 in the Donner’s Alder Creek encampment, but the details of her sad end will never be truly known. No trace of her was ever found except a

few artifacts such as her watch. Lewis Keseberg, the last survivor to reach Fort Sutter, is alleged to have eaten and possibly murdered Tamsen. He denied it, but rescuers found a pot of human flesh in the Murphy cabin where Keseberg had stayed and Tamsen allegedly had gone in a final and desperate attempt to get over the pass after George had perished. They also found George Donner’s pistols, jewelry and $250 in gold in Keseberg’s possession. Tamsen either died before she was consumed or was murdered. Who knows what depravity took place in the windowless tents the Donners occupied at Alder Creek as their desperate occupants hunkered down month after month, clinging to life. Or the sturdier but windowless cabins inhabited by the Breens, Murphys and other families.

A series of blunders doomed the Donner party. Few had experience at camping much less in blizzard conditions, hunting and navigation such as it was in the 1846. They never got crucial letters from Lansford Hastings urging them to avoid the cutoff with their heavy wagons. The route set them back weeks and put them at Donner well into the fall instead of in late summer. They also had just plain bad luck. Heavy snows came early in 1846, emptying the hunting grounds and making movement nearly impossible. Ann and I stood at a memorial to the Donners, the site of the Breen cabin where the snow was 22 feet deep. All members of the Breen family survived.

A comparatively healthy Tamsen could have left with a rescue party that arrived in mid Feburary, 1847, but refused to leave her husband who was dying from starvation and gang green in his arm injured while repairing a wagon. However, all five of their daughters made their way into California and collectively gave birth to 17 children, inspiring a poem by Ruth Whitman written in 1972. The Donner party still deeply affected people more than a century after the ordeal. The poem goes like this.

“If my boundary stops here,

I have daughters to draw new maps on the world

they will draw the lines of my face, they will draw with my gestures my voice

they will speak my words thinking they have invented them.

They will invent them, they will invent me,

I will be planted again and again,

I will wake in the eyes of their children’s children

they will speak my words.”

Whitman also published a book in 1977 where she retraced Tamsen’s route and like her subject, kept a diary. The experience prompted Whitman to say that she had known Tamsen all along.

Fast forward almost 20 years and arguably the most important civil engineering and construction project in the formation of our nation would change the pass forever. The Transcontinental Railroad that would be completed on May 10th, 1869. The driving of the golden spike, by the way, celebrated its 150th anniversary this year.

Judah, an RPI trained civil engineer, convinced the Big Four to invest in his crazy scheme to build over Donner. Judah also helped to persuade President Lincoln to sign the Pacific Railroad Acts on July 1, 1862, which would provide land and money for the newly formed Central Pacific R.R. in the far west and Union Pacific R.R. whose tracks would traverse Nebraska, Wyoming and Utah. The two lines would meet in Promontory, Utah.

Judah, a Bridgeport, Conn. native, would never see his dream of rails over the pass realized because he contracted yellow fever on a steamer headed for New York in 1863 and died. A peak adjacent to the Donner summit bears his name, but now trains go under Mount Judah instead of over the pass. Still, they emerge from tunnel 41 near the top of the pass.

Conquering the Donner summit required numerous tunnels, snow sheds and blasting right of way from sheer cliffs. This was done by largely by Chinese laborers who became known for a work ethic as solid as the rock they were chiseling away. Construction supervisor Charles Crocker originally thought the 50 Chinese workers hired in Feb., 1865 would not be able to hack the harsh conditions and demands of the work, but quickly changed his mind when they repeatedly proved themselves to be more reliable and hard-working than other ethnicities. By the fall, their ranks had swollen to 3,000 and 12,000 the following year.

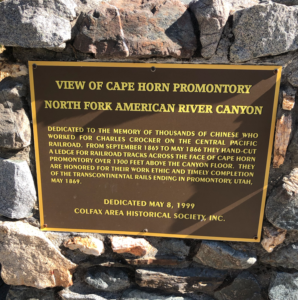

Our journey through Donner started about 30 miles west of the summit in Colfax. We stopped at the local trackside depot, which doubles as the Colfax historical society. Some friendly hosts pointed out Cape Horn, which starts the easterly ascent to the summit from the west. Here, using picks, hammers and chisels, Chinese laborers carved out 13 miles of roadbed above the North

Fork of the American River to Dutch Flats during the winter of 1865-66, according to the Placer Sierra Railroad Heritage Society.

We viewed Cape Horn, but could not see the railroad given the density of conifers. So we headed east on I-80 toward the summit. Over the next 20 miles, I didn’t see much of the railroad, fearful that I was missing something spectacular that I had come all this way to see. I mean we flew six hours across the country with no meal service. Tell that to Tamsen.

I stopped several times to get my bearings even though the scenery was becoming more spectacular as we climbed through names I knew from history – Dutch Flats, Emigrant Gap, Yuba Pass, Cisco and Soda Springs. As thick stands of conifers gave way to bald rocky outcroppings, my excitement grew as did my fears that we were speeding by something remarkable. Then I found the Donner Pass Rd. exit in Norden.

I was born too late and on the wrong end of the country. What I wouldn’t have given to be a Southern Pacific crew member stationed at Norden to clear snow from the tracks in massive rotary plows and to detach monster helper engines pushing trains up the tortuous grades from Truckee. Just below the summit, Norden played host to crew quarters, a restaurant and a huge turntable to send the Cab Forwards back down to Truckee for the next run up the Pass. Bright yellow Union Pacific diesel helpers are still stationed in Truckee.

Cab Forwards were massive steam locomotives with cabs in the

front of the boiler so the crews would enjoy more visibility around sharp curves and not be asphyxiated by smoke. I saw the only remaining cab forward – 200 were built – at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento. By steam locomotive standards, the cabs of these leviathans were relatively spacious and clean given they were oil burners.

We also saw the Governor Stanford, locomotive number one which helped build the Central Pacific and carried the first revenue freight on the line. It was built in Philadelphia in 1862 and shipped disassembled in crates around the Horn of South America to San Francisco. The museum’s collection of 19thcentury locomotives is priceless. None are replicas. They have been restored, but are the real deal.

In writing this paper, I realized we missed one of the four golden spikes commemorating the historic meeting of the two lines in Promontory. There were four golden spikes and the California Museum had the second one which was unknown to the public until 2005. The heavily etched original gold spike is on display at Stanford University and bears the names of the Central Pacific officers and a line whose first few words are prophetic given the current state of affairs. “May God continue the unity of our Country as the railroad unites the two great oceans of the world.”

Since the golden spikes were the creation of a San Francisco financier, the inscriptions focused on the Big Four and a couple of other Central Pacific big shots. I was hoping to read the name of distant relative and Danvers native Gen. Grenville Mellen Dodge. He was Union Pacific’s chief engineer and a major force in the first 250 miles west from Omaha. He also pioneered intelligence gathering during the Civil War and was labeled by his biographer Stanley Hirshon as more important to the Union effort than Grant or Sherman. He was an Indian fighter and congressman from Iowa where he known for bringing railroads to the state. Indeed, Union Pacific headquarters was located on Dodge St. in Omaha. (In 2016, the 100th anniversary of Grenville’s death, Omaha’s town officials debated whether to rename Dodge St., unsure if it was named after pro-slavery Union general Augustus Caesar Dodge (bad) or Grenville (good). It remains Dodge St. today.)

Interestingly, I recently discovered that my great, great grandfather father John L. Dodge had property holdings in Fort Dodge, Iowa. Another family avenue to investigate. It was named after Henry Dodge, a former governor of the Wisconsin territory.

The line’s ownership hasn’t changed much over 151 years. The Central Pacific was merged into the Southern Pacific under Crocker. It had more tunnels and snow sheds that any other railroad in the U.S. In 1988, Southern Pacific was taken over by the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad in a complex deal, but SP kept its name and eventually acquired the acquirer. In 1996, Union Pacific took over the Southern Pacific Transportation Company. For all intents and purposes, one of the nation’s most storied railroads with its handsome headquarters building on Market St. in San Francisco was gone.

My spirits brightened as we headed into Norden. Some of the snow sheds came into view fed by the remaining track from tunnel 41. We saw a couple of strategically placed bulldozers used in the prodigious snow fighting Union Pacific undertakes every year.

Today, the summit hosts several ski areas so we took a few turns into a condo development trying to find precisely where the railroad went over the summit. Nada. We drove on until we came to the 7,088 foot Donner Pass summit. “Ann, I think the line is just beyond those rocks. Give me a few minutes,” I begged. Her patience with my railroad adventures was wearing thin. I just don’t get why she wouldn’t love this stuff as much as me. “They’re just tracks. Why don’t you carry around some tracks for when you need a fix,” she sarcastically suggested.

I let that one pass and climbed over the rocks and eureka, there were summit tunnels from the legendary track one. My pilgrimage was complete, but far from over. As we wound down Donner Pass Rd. on the eastern side of the pass, long stretches of snow sheds game into view as well as a double stack container train creeping west toward the eastern portal of tunnel 41. We also

came upon the famed China Wall, a memorial to the Chinese laborers whose sacrifice and work cannot be overstated. Stanford later admitted the railroad would have never been finished on time without the Chinese workers. The 75-foot high rock wall fills a ravine between tunnels 7 and 8 just east of the summit.

Given the expense of maintaining the line, there had been talk 20 years ago of downgrading it and transferring traffic to other lines, but Union Pacific instead expanded its capacity. I hold out hope that track one will be restored over the summit if only as a tourist attraction. Union Pacific’s steam program, which just brought a Big Boy steamer back to life demonstrates UP’s commitment at keeping history alive. Big Boys were the largest steam locomotives ever made and assigned to the busy Overland Route (the Transcontinental Railroad) across southern Wyoming.

Our ride down Donner Pass Rd. concluded at Donner Lake where we enjoyed a picnic lunch. Then we were on to the Donner Party Museum.

So I can cross Donner off my bucket list, but I’d like to go back, maybe to hike the snow sheds or the five mile loop around Mount Judah. Richie Jones, perhaps you could pack up your palette and brushes and go work your magic on this most hallowed ground.

Today, the Donner Pass summit is a playground dotted with condos and chair lifts. Ringed by ski areas, including the site of the 1960 winter Olympics, Squaw Valley, Lake Tahoe is just to the south of Donner. The rail line is still busy as a major mid country route between Oakland and Chicago and Truckee is thriving as a tourist town.

I saw all that, but with deep reverence, I also heard the distinct echoes and voices of the past.

Sources: Wikipedia, Placer Sierra Railroad Historical Society, the stormking.com, PBS The American Experience, Google Maps, tahoetopia.com, Arounddonnersummit.com, UnionPacific.com, California State Railroad Museum, Donner Memorial State Park-Museum, several newspapers and stuff I’ve know for a long time.

2 comments On Donner Pass a Cathedral of American History

Excellent report. Just in awe. Tamsen Eustis Dinner was Abraham Wheelwright’s niece ( he lived in my Newburyport house). “Searching for Tamsen Donner” is a contemporary takeoff on Tamsen’s struggle and worth the read. Well done!

Thanks, Jack. I enjoyed doing it and traveling there.